TRILAB is an online platform, run by an Italian SME for the sale of cosmetics and other body-care products to consumers. Many of said products are renowned brands such as Wella, Kerastase, Collistar, and among the perfumes Dior, Estée Lauder, Paco Rabanne, Armani. There was once Chanel as well; but it is no longer the case. Why?

The fact is that Chanel adopts in Italy a selective distribution scheme, where only certain qualified subjects are allowed to distribute Chanel’s products. And TRILAB was not among them.

So, at the beginning of 2022 CHANEL filed a lawsuit against TRILAB before the business division of the Milan Courts to prevent TRILAB to further market CHANEL products. Apparently, TRILAB could rely on the fact that, once a branded product is put on sale in the EU (the EEA, indeed) by, or with the consent of the owner of the brand, said owner cannot prevent any further resale, save “legitimate grounds”, just because of the rights it has on the brand (so called principle of Trademark exhaustion[1]). And TRILAB had been supplied of the CHANEL products by an authorized CHANEL distributor.

CHANEL’s action, however, turned out to be successful. The Milan Court in their decision no. 2635 of Feb 28, 2022, in fact, held – in the framework of a petition of interim measures – that a selective distribution amounts to one of those special cases where the principle of trademark exhaustion cannot apply.

The existence of a selective distribution network may be included among the “legitimate reasons” precluding trademark exhaustion, provided that the marketed product is a luxury or prestige item that legitimizes the decision to adopt a selective distribution system, and that there is actual damage to the luxury or prestige image of the trademark as a result of the marketing carried out by third parties outside the same network. Altering the codes affixed to the packaging of luxury goods (in this case, cosmetics), as well as the manner in which such goods are presented by the retailer, on an e-commerce site for hairdressers, with blurred images and crowded content, are to be considered “legitimate reasons”, alongside products of a different merchandise nature and with lower profile brands (the fact, however, that the retailer never comes into possession of the products sold and does not have the material possibility of verifying the existence of the alteration does not exclude its liability since it offers for sale and markets such products).

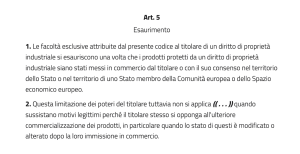

This is a matter of interpretation, though; since the EU law does not list which are the impeding “legitimate reasons”. It just hints at special cases of improper alterations (“especially where the condition of these is changed or impaire d after they have been put on the market” – sec 15(2) of the 2015 EU Trademark Directive that has been transposed verbatim in the Italian IPC – Industrial Property Code – art. 5(2)).

d after they have been put on the market” – sec 15(2) of the 2015 EU Trademark Directive that has been transposed verbatim in the Italian IPC – Industrial Property Code – art. 5(2)).

According to the ECJ in the case Boehringer (2007)[2] this occurs in case of “a new packaging of the product, which is likely to damage the reputation of the trademark and its owner, so the packaging or the label must not be defective, of poor quality, or untidy”) following ECJ C-337/95 (1997) in the case Dior v Evora (in which, Dior’s claim was rejected, not to be mixed with other non-luxury products)[3].

A difference instance is when products of different ‘level’ are mixed. This is the case of luxury (or any other costly) items are offered for sale together with other more commoners intended, so to say. It’s a matter of promiscuity, indeed. And the luxury brands are obviously sensible to that. Well, in these occurrences, it should be recalled that the ECJ held in 2009 in Copad v Dior that a licensee may be prevented from improperly marketing the licenced product (it was a matter of discounted prices) “provided it has been established that that […] damages the allure and prestigious image which bestows on those goods an aura of luxury”[4]. From another perspective (i.e. the concern of compliance to the EU competition rules), it was held in the Coty case[5] that a selective distributor of luxury products may be contractually prevented from marketing it through third-party internet platforms (such as Amazon or Ebay) “on condition that that clause has the objective of preserving the luxury image of those goods”.

Then, it evident that the fact that TRILAB would market the Chanel products online has been considered by the Milan court as an important factor, as it did in a 2019 decision in the case Sysley Parfumes[6]. In fact, some years ago, the Court of Appeal of Milan rejected a similar claim in a case where jewellery items were displayed outside the selective distribution network, in a brick-and-mortar shop, this being assumed as a non-that-outrageous market channel[7].

In conclusion, it seems that the business division of the Milan Court is of the opinion that the mere fact that a selective distribution system is in place may be of great obstacle for any out-of-system e-commerce traders to compete.

Those who are interested in receiving (free) full copy of the annotated decisions, please write to newsletter@lexmill.com.

____________

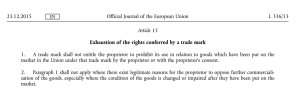

[1] The trademark exhaustion doctrine as established by the ECJ traces back in 1964 in the famous Consten v Grundig 1966 decision (joined cases 56/64 and 58/64) and eventually incorporated into Article 7(1) of the 1st Trademark Directive 89/104 (“[T]he trade mark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit its use in relation to goods which have been put on the market in the Community under that trade mark by the proprietor or with his consent.”).

The rule can now be found in art. 15 of TM Directive 2015/2436: “A trademark shall not entitle the proprietor to prohibit its use in relation to goods which have been put on the market in the Union under that trademark by the proprietor or with the proprietor’s consent”. It is now incorporated in the Italian law at sec. 5 of the Industrial Property Code.

[2] ECJ decision 26/04/2007 in C-348/04 Boehringer v Boehringer.

[3] ECJ decision 04/11/1997 in C-337/95 Dior v Evora.

[4] ECJ decision 23/04/2009 in C-59/08 Copad v Dior at alii.

[5] ECJ decision 06/12/2017 in C-230/16 Coty Germany v Parfümerie Akzente.

[6] Tr. Milan bus. div. decision 03/07/2019 in Sysley Parfumes: “The sale of luxury products (in this case, Sysley brand fragrances) through an online marketplace such as Amazon, where such products are displayed and offered among other items, such as microwave containers, household and floor cleaning products, and pet care products, of low profile and low economic value, as well as juxtaposed with low-end brands of much lower quality, The presence of links leading to completely different product sites and the absence of adequate customer service, such as the presence in the physical store of a person capable of adequately advising or informing consumers, results in damage to the luxury image of the mark and therefore constitutes a legitimate reason to oppose exhaustion.”

[7] C Appeal Milan (IT) decision no. 4683 of 25/11/2019 in the case Chantecler v Gens Aurea: “The marketing of a luxury product, such as a piece of jewelry of fine workmanship, resold within a selective distribution system by a store outside that system and placed within an outlet does not in itself harm the reputation of the brand, either by the fact that it proposes its commercial offer to the general public, that is, to a very large and non-exclusive clientele, where it turns out that even authorized distributors because of their location in the thoroughfares of large cities, direct their proposal to a similar number of people who do not differ from the general public that also frequents outlets, nor by the fact of systematically charging lower prices than those of authorized retailers, the setting of a minimum resale price being a practice that is not permitted, not even for the purpose of ensuring brand protection for the product in the event that it is distributed by a lawful selective distribution system”. The decision had been recently upheld by the Court of Cassation (decision 7378/2023) even though their reasoning appears flimsy indeed: in the eyes of the Cassation court, in fact, no selective distribution system had been detected by the lower court (?!?), therefore no ‘legitimate reason’ for exemption occurred.